An Armful of Bios

September 16, 2025

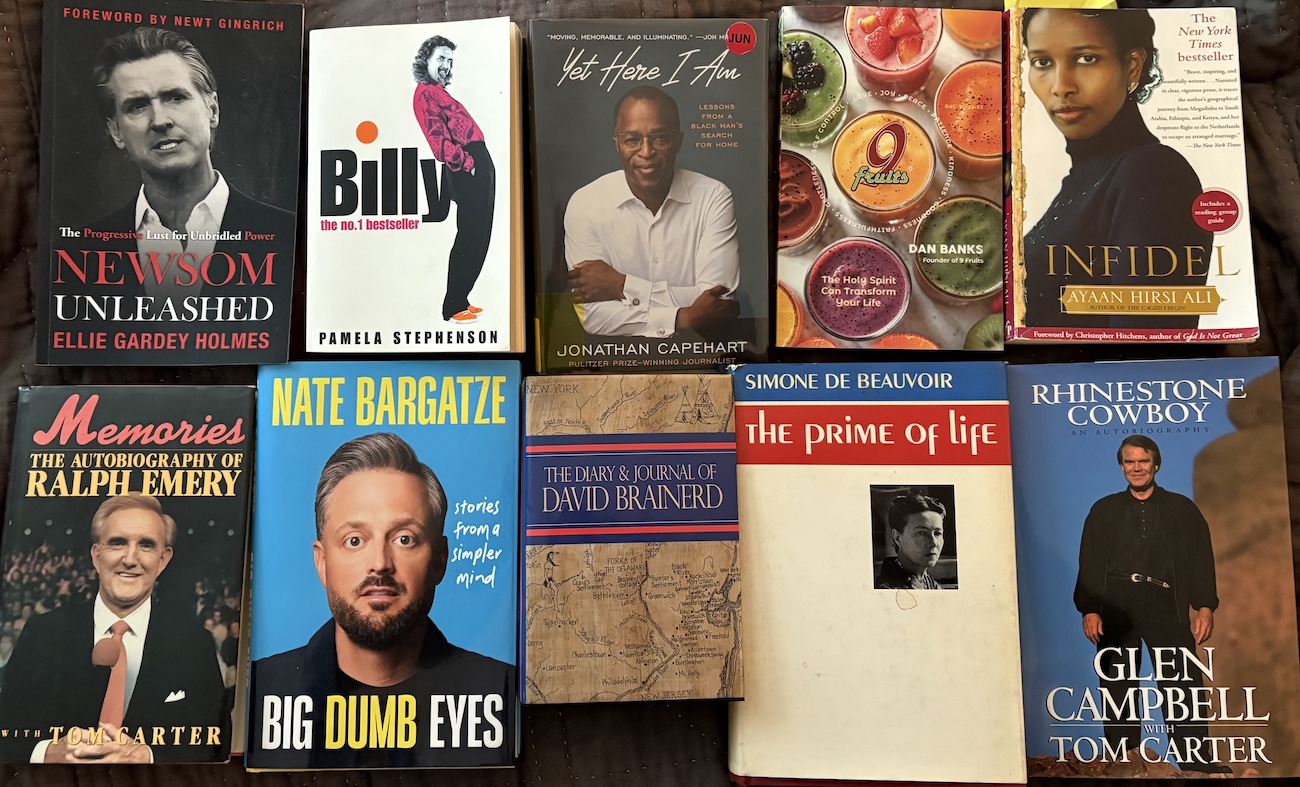

I love to read biographies, and here are notes on a batch of ten, one (Capehart’s) from the Brentwood library, the others from my own collection.

Newsom Unleashed: The Progressive Lust for Unbridled Power, by Ellie Gardey Holmes (Bombardier, 2025)

Ellie is the associate editor of The American Spectator, which has posted some of my writing. Here, with a foreword by Newt Gingrich, she’s told with great and convincing detail how awful California’s governor, Gavin Newson, is. She makes out the case that he’s not even fit to be dogcatcher, and it’s astonishing that he would style himself as a potential US president.

Summarizing the first five chapters, she writes, “Newsom played with fire in his first term when it came to his personal life. He had divorced his wife [Kimberly Guilfoyle, who became a regular on Fox’s The Five and also a Trump fundraiser], cheated with a married mother, dated a teenager, and announced that he had a drinking problem.” Nevertheless, “[f]or San Franciscans, the untoward behavior and lies were non factors. Their mayor was fascinating and progressive—and they liked it.” He was also essentially adopted by the vastly wealthy Gordon Getty (grandson and heir of the late, fabulously wealthy, John Paul Getty), was a protégé of the same power-broker Willie Brown who also gave Kamala Harris her start, and blessed with good looks—a glib communicator and a chameleon on plaid when he need to shift positions to please his “progressive” constituency.

As mayor San Francisco, he became the celebrity pioneer of gay marriage, authorizing such licenses for the first time in US history. The city held nine hundred of these ceremonies over Valentine’s Day weekend 2004, and he invited the celebrity Rosie O’Donnell to travel to his fair city to wed her longtime partner. He said the opposition would also be opposed to inter-racial marriage.

His second marriage was to actress and documentary filmmaker Jennifer Siebel, who, in 2022, joined with Harvey Weinstein’s accusers, saying that he had lured her into his “lair” for sex in 2005. The defense said it was consensual and that they had had amiable communication thereafter. But, whatever. The Newsom wedding was performed by Carol Simone, “a woman who says she possesses skills in astrology, Chinese energetic medicine, clairaudience, color therapy, Ho‘oponopono, hypnotherapy, meditation, metaphysical arts, numerology, past-life regression, Reiki, shamanic healing, sound healing, and tarot.”

You can’t make this stuff up. Indeed, that’s the tenor of the book. It’s astonishing throughout, as Newsom stomped his way unto COVID shutdown madness; made shoplifting up to $950 a misdemeanor; generated sky-high energy prices, rents, and unemployment; saw a homeless population grow to 171,500; nurtured a water crisis and wildfire threats; countenanced 11,000 deaths a year from drug abuse; effected a two-year, population drop of more than 500,000 (even with open border to the South); and, between 2018 and 2021, watched as 352 businesses moved their headquarters out of state, 11 of them among the Fortune 1000.

In short, Newsom is a reptilian disaster. And, though it was a tough read to handle page-after-page horror, I’m grateful to Ellie for spelling things out.

Billy, by Pamela Stephenson (HarperCollins, 2001)

The first time I became aware of Billy Connolly was when I saw the film, Mrs. Brown, in which he played, John Brown, the Scottish attendant to Queen Victoria in her grief following the loss of her husband, Prince Albert. The film title comes from a slight that emerged in the day—that she was so dependent upon and friendly with him that she, in effect, became his wife.

Connolly played the part with “Victorian” dignity, and I didn’t, at the time, suspect that he was also a musician and comedian (an often-nasty one). He’s much given to the F-bomb, and in this book, written by his second wife, she chronicles seventy-six of them (a forthcoming tally she announces in the opening, and then delivers at the end).

She covers his Glasgow upbringing, which was pretty awful, and notes his experience with the Catholic church, which helped to leave him an atheist (though there was enough in his fallen nature to get him there without it). He’s made his way through shipyard welding and folk singing and a host gigs to gain knighthood from the queen and a honorary degree from Glasgow University.

In the book’s epilogue, we read some of his “desiderata,” to include:

If you must lie about your age, do it in the other direction: tell people you’re ninety-seven and they’ll think you look [expletive omitted] great.

Never turn down an opportunity to shout, “[expletive omitted] them all!” at the top of your voice.

Before you judge a man, walk a mile in his shoes. After that, who cares? . . . He’s a mile away and you’ve got his shoes.

If you haven’t heard a good rumour by 11:00 a.m., start one.

Learn to feel sorry for music because, although it is the international language, it has no swearwords (if you don’t count Wagner, which in my opinion is one long one and should be avoided at all costs)

Salute nobody.

Avoid giving LSD to guide dogs.

Send Hieronymus Bosch prints to elderly relatives for Christmas.

Yet Here I Am: Lessons from a Black Man’s Search for Home, by Jonathan Capehart (Grand Central, 2025)

I found this on the new arrivals shelf at the Brentwood library, and it looked to be more grist for my mill, as I’m working on a book I call “I Heard a Dream.” It plays off MLK’s famous speech and I honor the notion of “colorblindness,” which King espoused and which is thoroughly despised today. This particular book is one of a gazillion cranked out in the black-grievance mode, and I wanted to see if he had anything fresh to say. From the front cover, you can tell his is a success story, and from the back cover, you can tell his narrative fits the prevailed-over-racism trope, with commendatory blurbs from such reliable mainstream personalities as Katie Couric and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Capehart is gay and has won a Pulitzer. We learn early on that his father and stepfather were terrible people, but he was able to find some father substitutes along the way. As for his father, we read

Why did Capehart abandon us? Joe told me that my father loved to dance, and when the doctors told him that his blood clots required amputation of one of his legs, he said, “I was born with two legs and I’m going to die with two legs.”

“He decided he was going to live a fast life until he died, and he did,” Joe said. He left Margaret before you were born.” (p.13)

As newlyweds, his parents moved from North Carolina to Brooklyn, to life with his mom, where “she settled after she left her husband and family Down South.”

His grandma, who marinated him in Jehovah’s Witness culture,

. . . drilled into me a sense of humility. Not the kind where you downplay your skills or accomplishments, but the kind that guards against arrogance. I take nothing for granted, not the success I’ve achieved or the life it affords me, which serves me well in a world where the laws of gravity that many white people escape effortlessly apply doubly to Black folks. Good fortune can go south, and high public regard can plummet. Second chances aren’t guaranteed. The benefit of the doubt is parsimoniously given, if ever.

Then, there is white envy of Black success. From an early age, I remember my mother and relatives saying some variation of, “They will only let a Black man rise so high or get away with so much or go so far.” This belief was the foundation for every explanation of any scandal or hardship to befall anyone Black of prominence. Myriad examples of white envy of Black success abound in America. Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898. Atlanta, Georgia, in 1906. The most famous manifestation of it is the destruction of Black Wall Street in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma, during a two-day white supremacist-led race riot in 1921. Protection of white womanhood in the face of false accusations of sexual harassment or violence was often the pretext for killing Blacks and pillaging their communities.

Over the ensuing generations, these experiences—and countless contemporary tragedies involving law enforcement and vigilantes—have made Black folks experts in white fear and insecurity. The fear of what white people are capable of lurks just below the surface of every Black person. (p. 33)

9 Fruits: The Holy Spirit Can Transform Your Life, by Dan Banks (self-published)

Sharon was very kind to sign me up for a daily free drink at a local restaurant (hazelnut coffee, my favorite), and I spend a fair amount of time there, working on different writing projects (and ordering other stuff to consume, which was the purpose of their free-drink setup). I’ve met some fascinating people there, including a man who tracked down wacky video clips for TV programs showing folks in various states of self-destruction; a realtor who put a sign on his table offering free home estimates; and a high school soccer team down from the DC area for a tournament.

One patron caught my attention because he was there most every day, hard at work on a computer with a big screen, festooned with some trinkets and a big feather. I had to ask, and I learned that he did IT stuff for folks and that he had a fascinating church background. And, in addition to his keyboard magic, he hosted rotating groups of men to discuss theology, AI, evangelism among Kurds, etc. The Saturday morning session I attended worked its way into talk about the philosopher Spinoza (whose work I’d recently lectured upon in my modern philosophy class at New Saint Andrews).

One day, Rob (the computer maven) brought a fellow named Dan Banks to my table to introduce us. He was a fascinating fellow, who’d moved to Middle Tennessee from California and established a smoothie business by called “9 Fruits” (named after the fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5). It’s been quite a journey, and not just the cross-country drive. He has an extensive background in business, having worked for years for Proctor & Gamble. He’s also been a competitive bicyclist, with strong showings in elite races, but he races no more.

Big shifts, but not as great as his spiritual transition, which he ties to six “wake-up calls,” including a near-miss on a Bay Area bridge (where an earthquake collapsed the roadway not long after he’d passed under it), several bike breakdowns during races, an injury to a child, and threatened divorce by his wife. At the point of despair, he cried out to God, and the Lord worked through a range of people and circumstances to rescue him and his family from lostness and dissolution. The list of people who have arrested and blessed their attention, whether directly or indirectly, includes James Dobson, Zig Ziglar, Tim Tebow, Steven Curtis Chapman, and Darrel Waltrip. Along the way, they became fruit-orchard tenders and home builders in the California countryside; inventors and purveyors of wonderful fruit drinks, e.g., the “Mighty Mocha” (coffee and cinnamon with cocoa, bananas, and frozen yogurt) and “Peach Flamingo” (peaches and mangos, with mango and frozen yogurt); and compelling witness to the saving grace of Christ.

I write this under “Browsings,” but I read the whole book in a couple of days. An edifying page-turner.

Infidel, by Ayaan Hirsi Ali (Free Press, 2007)

Over a decade ago, I used this book as one of several texts for a course surveying ethical systems worldwide. Taking it up afresh, I saw that I’d put a number of post-it notes in it, and I thought I’d run back through the book to see what it was that led me to put markers where I did.

As a Somali, she found herself in the Muslim Girls’ Secondary School in Kenya. Her breakdown of religions, tribes, and classes was fascinating. “The Pakistanis were Muslims, but they, too, had castes. The Untouchable girls, both Indian and Pakistani, were darker-skinned. The others wouldn’t play with them because they were Untouchable. We thought that was funny— because of course they were touchable: we touched them, see?—but also horrifying, to think of yourself as untouchable, despicable to the human race . . . Some of the Arab girls had clans, as we did. If you were a Yemeni called Sharif, then you were superior to a Yemeni called Zubaydi. Any kind of Arab girl considered herself superior to everyone: she was born closer to the Prophet Muhammad.” (68)

“Love marriages were a stupid mistake and always ended badly, in poverty and divorce; we knew this. If you married outside the rules, you didn’t have your clan’s protection when you husband left you. Your father’s relatives wouldn’t intercede on your behalf or help you with money. You sank into a hideous destiny of impurity, godlessness, and disease. People like my grandmother pointed at you and spat at you on the street. It was the worst thing you could do to your family’s honor: you damaged your parents, sisters, brothers, and cousins.” (79)

“Everyone was convinced that there was an evil worldwide crusade aimed at eradicating Islam, directed by the Jews and by the whole Godless West . . . Our goal was a global Islamic government, for everyone . . . As much as I wanted to be a devout Muslim, I always found it uncomfortable to be opposed to the West. For me, Britain and America were the countries in my books where there was decency and individual choice.” (108-109)

She got a job as secretary for a small office of the United Nations Development Program, one that was set up to establish phone lines into rural Somalia. Her boss, a “rather bewildered Englishman” would meet with a delegation from the provinces, and I would try to explain why he wouldn’t just give them the cash to set up a phoneline. He would also try to explain why they shouldn’t tear up and resell the cables he’d just laid, while they ignored him and talked among themselves. He had no authority over his staff, but this was a so-called multilateral project, so he was under orders to respond their views and their way of doing things even if they had neither view nor methodology. . . Working also gave me a close-up look at the Somali bureaucracy. Almost every civil servant I encountered seemed abysmally ignorant. Their scorn for all thing gaalo, including my boss, was profound (Gaalo unsually means “white unbeliever,” but not always. Ma used this word for the Kenyans, too.) They were completely uninterested in doing their jobs, and spent their time scheming about how to “transfer” government funds, a euphemism for stealing them. In Somalia, to have a stake in government was to have a family member in the place where tax money and money from kickbacks was distributed. No more, no less. I saw what that does to a nation: it destroys public trust.” (133)

She made her way to Germany, where a distant uncle committed to look after her. She was astonished by the order, cleanliness, and comforts of Dusseldorf. Back in Kenya, she had seen Mercedes cabs only in front of the most exclusive hotels, so she asked the airport cabby if his Mercedes was the one she’d be a passenger in. Checking into the hotel, she found everything “white and pristine,” small, but with “all somehow cleverly planned to fit: the closets fit into the wall, the TV inside a cabinet.” Back in Kenya, they had a showers, “but it never had hot water, so [they]boiled water and used a pail and a scoop. Here was hot water, tons of it, in different jets from above and from the sides.” Out on the street, she was struck by the appearance of the women, whose legs, arms, faces, hair, and shoulders were uncovered. . . After a little while, I took my coat off; I thought I might stick out less. I still had on a headscarf and a long skirt, but it was the most uncovered I had been in public for many years . . . No eyes silently accused me of being a whore. No lecherous men called me to bed with them No Brotherhood members threatened me with hellfire.” (184-185)

Later, in the Netherlands, she was puzzled: “This was an infidel country, whose way of life we Muslims were supposed to opposed and reject. Why was it, then, so much better run, better led, and made for such better lives than the places we came from? Shouldn’t the places where Allah was worshipped and His laws obeyed have been at peace and wealthy, and the unbelievers’ country ignorant, poor, and at war? . . . What was wrong with us? Why should infidels have peace, and Muslims be killing each other, when we were the ones who worshipped the true God?” (222)

“It irritated me now when Somalis who had lived in Holland for a long time complained that they were offered only lowly jobs. They wanted honorable professions: airline pilot, lawyer. When I pointed out that they had no qualifications for such work, their attitude was that everything was Holland’s fault. The Europeans had colonized Somalia, which was why we all had no qualifications and were in this mess to begin with. I thought that was so clearly nonsense. We had torn ourselves apart, all on our own . . . Here in Holland the claim was always that we were held back by racism. Everyone seemed to be in a constant simmer of anger about how we were discriminated against because we were black. If a shopkeeper wouldn’t bargain over the price of a T-shirt, Yasmin said there were special, discount prices only for white people. She and Hasna told me they often didn’t bother paying for buses; they just invented appointments in town, and if the refugee office didn’t give them a ticket, they said they were being racist. ‘If you tell a Dutch person it’s racist, he will give you whatever you want,’ Hasna once to me with satisfaction. There is discrimination in Holland—I would never deny that—but the claim of racism can also be strategic.” (224)

If Muslim immigrants lagged so far behind even other immigrant groups, then wasn’t it possible that one of the reasons could be Islam? Islam influences every aspect of believers’ lives. Women are denied their social and economic rights in the name of Islam, and ignorant women bring up ignorant children. Sons brought up watching their mother being beaten will use violence. Why is it racist to ask this question? Why was it antiracist to indulge people’s attachment to their old ideas and perpetuate this misery? The passive, Insh’Allah attitude so prevalent in Islam—“if Allah wills it”—couldn’t this also be said to affect people’s energy and their will to change and improve the world? If you believe that Allah predestines all, and life on earth is simply a waiting room for the Hereafter, does that belief have no link to the fatalism that so often reinforces poverty?” (279)

“In October 2002, I flew to California. It was the first time I had ever been in the United States, and I realized almost immediately that my pre-conceptions of America were completely ludicrous. I was expecting rednecks and fat people, with lots of guns, very aggressive police, and overt racism—a caricature of a caricature. In reality, of course, I saw people living perfectly well-ordered lives, jogging, and drinking coffee. (293)

Memories: The Autobiography of Ralph Emery, with Tom Carter (Macmillan, 1991)

Ralph Emery, who was a huge Nashville presence in my grad school days, did this book with the same man Glen Campbell used for Rhinestone Cowboy, Tom Carter. Carter did a good job in delivering these men’s accounts. And the book jacket said this particular story was well worth telling: Chet Atkins said, “There is no greater authority in country music”; Johnny Cash added, “Ralph Emery was the first person to bring dignity and education to country music radio.”

It was an engaging read, so much so that my “browsing” turned into regular reading past 150 pages of this 273-page book, this on the heels of a total-read of the Glen Campbell book. But there was a difference: While there was an amiable and ultimately uplifting feel to the former, the Emery book was more cranky and braggy. Now and then, he’d preface his remarks by saying he needed to go ahead with jabbing someone in the interest of honesty, but he was too ready to drive things in the direction of tabloid gossip. (“ . . . I’ve been told that my credibility as an autobiographer will suffer if I don’t address a headline-grabbing marriage that rode a roller coaster of emotions.”) He goes on to say, “I thought about including a chapter here, with a headline reading, ‘Things I Enjoyed About My Marriage to Skeeter Dave.’ I was going to leave the pages blank.”

I imagine a fair number of the targets rightly assumed that stumbles in their life and work alongside Emery would fall within some sort of zone of privacy. Silly they. (Not sure he did himself or us a favor noting the petty jealousy of Jim Reeves and boozy lapses of Patsy Cline.)

To be sure, Emery was self-effacing at many points, often admitting to the insecurities that came from a woeful childhood (and he is quite eager to place blame for the woes on others). He speaks freely of “suffocating . . . despondency,” born in low self-esteem, of his descent into alcohol and amphetamine abuse. Elsewhere, he ties his exhausting work ethic to “vivid memories of childhood poverty,” driving him to “seize almost every opportunity to earn money.” But he manages to spin most of his disappointments into the gold of a fetching narrative, one in which he throws under the bus, for instance, his father, former wives, a “brown noser” who worked at the station, and a Grand Ole Opry director,

He’s harsh on the urged conversion and baptism of young people and the SBC, which he accuses of “verbal fighting and friction” and “taking their eyes off Christ” (a shot at the “conservative resurgence,” which was strongly opposed by the Sherman brothers, Cecil and Bill, with Bill being Emery’s pastor at Nashville’s Woodmont Baptist Church). But, he does have kind words to say about a pastor who talked him out of shooting his wife’s boyfriend, and for singers Marty Robbins and Tex Ritter

Along the way, there are some fascinating tidbits, e.g., that, back in the day, any use of a ‘damn’ or a ‘hell’ in a song could deny it airplay; that famous Texas fiddle player Bob Wills would sometimes be so drunk his band members would have to prop him up in a chair onstage in hopes they’d be paid for a Bob Wills appearance; and that Hank Williams’s Opry debut “stopped the show colder than it has ever been,” what with the long-running applause

All told, Campbell’s book was an “upper,” Emery’s a “downer.” But an interesting one, especially for someone who’s spent years around the Nashville, country-music scene.

Big Dumb Eyes: Stories from a Simpler Mind, by Nate Bargatze (Grand Central, 2025).

When we were in Idaho, we started sampling standup comics on Netflix, and, not surprisingly, we found that the overwhelming majority of them “worked blue,” delivering nasty material with the obligatory scatological vocabulary. Whether the stream of F and S Bombs was meant to trigger naughty laughter from the audience or that’s just the way these guys (and gals) thought and talked, or both, it was everywhere. Not so with Nate Bargatze, who hails from our neck of the Middle Tennessee woods. Raised in Old Hickory and based now in Mount Juliet, 15 miles from my birthplace in Lebanon (where my dad was teaching at a once-Baptist School, Cumberland University, and pastoring Immanuel Baptist Church). And I recognized the surname ‘Bargatze’ from my grad school days in Nashville. His uncle, Ron Bargatze, was an assistant basketball coach at Vanderbilt, the one who recruited some amazing players we were delighted to cheer in my grad school days.

In those videos, “Nate” told some wonderful stories in his deadpan, childlike way, e.g., about the donkey at the fair who jumped/fell from a platform into a pool of water; the night after 9/11 when the water department had him stand with a lantern near the city water tower, watching for a terrorist attack; his ignorance of history, meaning he sat on the edge of his seat at a WWII movie, wondering what was about to happen at Pearl Harbor.

Now, he’s picked up the story with a book. There’s some overlap here and there, but the vast majority of the material is new, filling in a lot of gaps with the same sweet amazement at what transpired. It’s not knee-slapping stuff, but rather an account with charming innocence. For one thing, he picks up on his stand-up routine’s admission that he had a tough time reading, what with all those words on every page. He wished they’d insert some blank ones now and then so he could catch his breath; and, sure enough, Big Dumb Eyes, provides them, as at pages 96-98 and 186-188.

His grammar is regionally challenged, and his recollections are ironic, as when he comments on a photo from the time they slept with a stray dog that lived on the garbage in the neighborhood:

Me and Derek are sound asleep, and the dog has this wide-eyed look on his face like, “Well, this happened.” We didn’t know if he had fleas, we didn’t know if he had rabies, we didn’t know if he had a name. The most we did was call him “Black Dog,” because he happed to be a black dog.

And then he recalls a big moment at McDonald’s:

When I was born back in the 1900s, McDonald’s wasn’t just a place to go when you were in a hurry or there was nothing better—it was an actual restaurant. A special destination, a treat that real people went to just became they liked going there. Getting your first Big Mac was a rite of passage. Like, “I am finally big enough to eat this sandwich with two whole patties. I do not know what is in this special sauce, but I do know that eating it makes me a man.”

Throughout, he’s self-effacing, and he talks freely about church and faith. In this connection, he works “clean.” I’m not saying he’s a David Brainerd, but he’s not ashamed of his ecclesiastical connections. For one thing, his dream of playing in the NBA was realized by participation in the Nashville Baptist Association church hoops league.

Amazingly enough, he’s not just a figure on the “corn pone” circuit. He’s the most successful standup comedian in the land, filling arenas and appearing twice on Saturday Night Live. Who knew it would come to this?

The Diary & Journal of David Brainerd (Banner of Truth, 2007)

This a classic work of Christian devotion was first published in 1746, and his biography (by Jonathan Edwards, in whose home he died of tuberculosis when he was twenty-nine) furthered the admiration this young man’s self-sacrificial service has garnered from Evangelicals through the years. His service among the Indians ran from 1742 to 1747. In this brief selection, we see their attempts to alleviate sickness. Its futility underscores the fact that the gospel brings not only salvation, but also Western/Judeo-Christian civilization with its esteem for scientific medicine.

Many of the Indians of this island understand the English language very well, having formerly lived in some part of Maryland, among or near the white people; but they are very vicious, drunken, and profane, although not so savage as those who have less acquaintance with the English. Their customs in divers respects differ from those of other Indians upon this river . . . Their method of charming or conjuring over the sick seems somewhat different from that of other Indians, though for substance the same; and the whole of it, among these and others, is perhaps an imitation of what seems, by Naaman’s expression, 2 Kings v. 11, to have been the custom of ancient heathens. For it seems chiefly to consist in striking their hands over the diseased, repeatedly stroking them, and calling upon their gods, excepting the spurting of water like a mist, and some other frantic ceremonies common to the other conjurations, which I have already mentioned.

The Prime of Life, by Simone de Beauvoir (World Publishing, 1962).

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) is the most famous of atheistical existentialists, the one who said that the central idea of his philosophy was that, when it came to mankind, “existence precedes essence.” Unlike paper cutters, whose purpose is established before the first one is produced, humans are unique in that they come into being first and then are masters of their own makeup. They define themselves by their choices—not by enlarging upon, neglecting, or suppressing their “human nature,” for there is no such thing. It's a dismal prospect as we’re cast into “absurdity,” prone to disorienting, metaphysical “nausea,” realizing the “hell is other people.” (These are themes in his work.)

It would take a world-class fool of a woman to fall for such a world-class fool of a man, but Simone de Beauvoir filled the bill, as this selection from her memoir shows. Through her 1949 book, The Second Sex (banned by the Vatican), she deemed traditional/biblical marriage and childbearing a form of bondage, and thus became a powerful influence on the secular feminism that shapes out culture. But, reading this passage, it’s hard to see how she, as his “girl,” is any position to commend a lifestyle, a woman who accommodates the promiscuity of a man determined “to know the world and give it expression,” (a dressed-up expression to cover degeneracy).

Sartre enjoyed himself at the Institute, where he rediscovered the freedom and, to some extent, the camaraderie which had made him so fond of the Ecole Normale. In addition, he formed there one of those relationships with a woman by which is set such store. One of the resident students, whose zest for philology was only equaled by his indifference to passion, had a wife whom everyone at the Institute found charming. Marie Girard had been around the Latin Quarter for ages; in those days she had lived in shabby little hotels, shut away in her room for weeks on end, smoking and dreaming. She had not the slightest notion of what the purpose of her existence on this earth might be; she lived from one day to the next, lost in a private fog which only a few stubbornly irrefragable realities could penetrate. She did not believe in misfortunes of the heart or the afflictions that spring from luxury and riches. In her eyes the only real misfortunes were misery, hunger, physical pain; and as for happiness, the word simply had no meaning for her. She was an attractive, graceful girl, with a slow smile, and her pensive, abstracted daydreaming aroused a sympathetic response in search. She felt the same about him. They agreed that there could be no future in this relationship, but that its present reality sufficed: accordingly, they saw a good deal of each other. I met her, and liked her; there was no feeling of jealousy on my part. Yet this was the first time since we had known one another that Sartre had taken a serious interest in another woman; and jealousy is far from being an emotion of which I am incapable, or which I underrate. But this affair neither took me by surprise nor upset any notions I had formed concerning our joint lives, since right from the outset Sartre had wanted me that he was liable to embark on such adventures. I had accepted the principle, and now had no difficulty in accepting the fact. To know the world and give it expression, this was the aim that governed the whole of Sartre’s existence; and I knew just how set he was on it. Besides, I felt so closely bound to him that no such episode in his life could disturb me. (148-149)

Rhinestone Cowboy: An Autobiography, by Glen Campbell with Tom Carter (Villard, 2001)

I grew up in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, where my dad was a professor at Ouachita Baptist University (“College,” when he started in 1954). The little town of Delight was about 30 miles, out in the country. Glen Campbell often lists it as his hometown, but it was really the “big city” about six miles east of his real birth place and the place he is buried today—Billstown. He came into this world in 1936 and left it in 2017, felled by Alzheimer’s. The family was “dirt poor,” and I was reminded of J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy as I learned of his roots. Unlike Vance, Campbell was blessed by a drug-free, church-going family, but his were the sort of people who could have used some “three-dog nights” along the way (one so cold you had to throw them in bed to stay warm). BTW, Sharon and I used VetTix to recently attend a Three-Dog Night concert in Nashville, a joint appearance with the Little River Band. And yes, to my satisfaction, they sang “Never Been to Spain.”)

This book is another instance of my pressing beyond mere browsing to read the whole thing. It’s a great, self-effacing narrative. It tells the story of Campbell’s rise to stunning popularity, with his own TV show, multiple top hits, service as a Beach Boys fill-in and as a backup musician for a Frank Sinatra studio recording, appearance in a film with John Wayne, a golf tournament bearing his name, his own theater at Branson, and a performance before the queen of England. On the other hand, he was married four times, was tortured by his embrace of alcohol and cocaine, and was ensnared by his unmarried, unholy relationship with rising country star Tanya Tucker.

He had enough of the Christian narrative of his youth to read the Bible and “preach” to others, even while he was a terrible mess. But then, as he tells it, in his fourth marriage, with a baptized-as-a-youth but wayward wife, he found his way to renewal (or rather “newal”) in the Lord, thanks in part to the ministry of an SBC church, North Phoenix, pastored by Richard Jackson. Along the way, the book is peppered with anecdotes about those in the “industry.” Many are told on his disgraceful self. Others lift up and/or rank down some very familiar names. But, in the end, he recounts what appears to be a genuine conversion, and reports on his work against abortion, on his appearances with James Robinson, Pat Robertson, and Robert Schuller, and on his appreciation for the work of the ACLJ.

The story is rich in memorable detail, e.g.,

Dropping out of school in the seventh grade, he headed out West to start playing guitar in clubs and on radio with his mentor. When they started drawing crowds away from other establishments, the rivals would tell the cops that Glen was only fifteen, and they had to move on.

Though he became a member of a much-in-demand studio band in Los Angeles, he never learned to read notes, just chords.

A lot of musician acquaintances were using drugs to elevate their performances and to stay awake on the road, but one experiment was enough for him. High on one (an “L A Turnaround”), he was driving from Phoenix to LA when he had a flat tire. He was shaking and unfocused, and he had a tough time manipulating the jack and wrench. And then, addled, he drove off, leaving them and a hubcap behind.

And I love the quotes he drops in along the way, e.g.,

Re tabloids, “They lie so much, they have to hire somebody to call their dogs.”

Quoting Roger Miller: “I’d give my right arm to be ambidextrous.”

PS: When I was a first-year grad student in philosophy at Vanderbilt, I got to see a taping of the Johnny Cash show at the Ryman. Campbell was one of the guests, and when he came up into the balcony to mingle with the crowd, I got to shake his hand.